Net Working Capital in the M&A process

In M&A transactions (share purchases), Net Working Capital (“NWC”) plays a pivotal role in determining the final purchase price. NWC and the associated purchase price adjustment mechanisms are essential components of most deals and can significantly influence the final equity valuation. When properly structured and effectively implemented, the NWC adjustments help protect the interests of both parties and contribute to a fair and balanced transaction outcome.

However, based on our experience, the concept of NWC is often misunderstood and sometimes misapplied, particularly in smaller transactions. It is crucial to recognize that determining NWC is not purely a technical exercise. The calculation and its outcome are influenced by a combination of market practices and business-specific characteristics, culminating in a negotiated agreement between parties.

Definition of Net Working Capital and Its Role in Purchase Price Mechanics

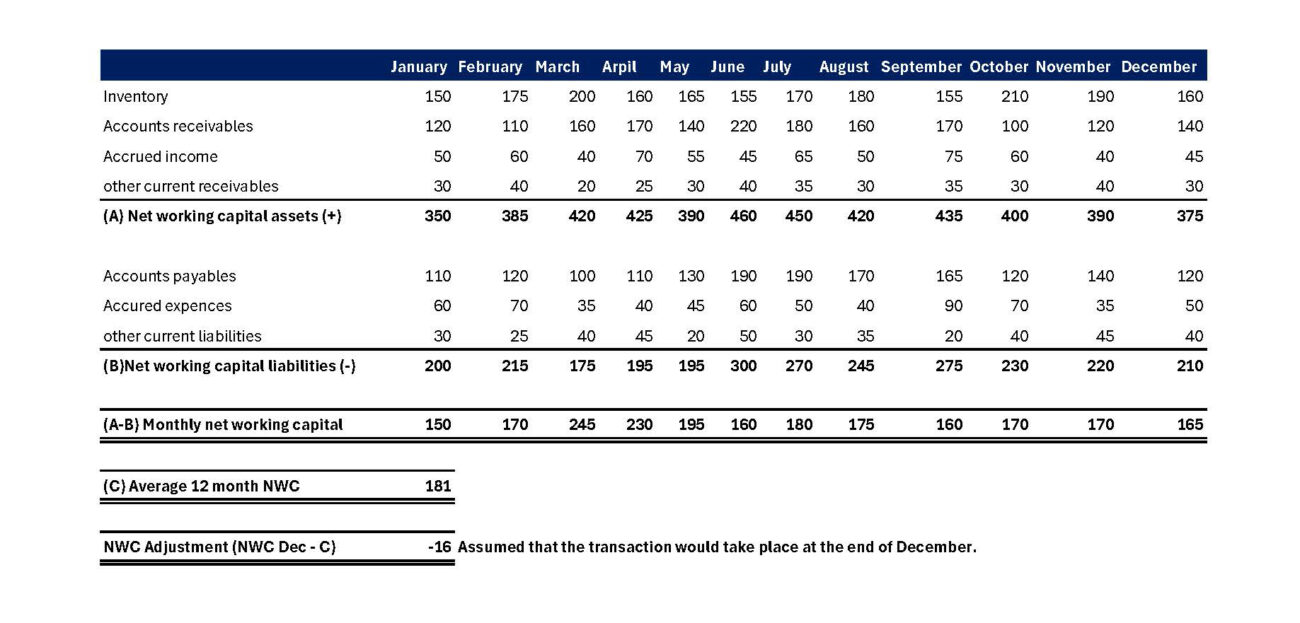

At its core, NWC typically consists of short-term assets specifically designated as working capital items (such as accounts receivable and inventory) minus short-term liabilities (such as accounts payable and accrued liabilities). The purpose is to evaluate the level of NWC typically required to operate the business on a normalized basis, often by reviewing average balances over a 12-month period.

In a professionally managed M&A process, the buyer typically proposes an initial estimate of the “Normalized NWC.” Based on this proposal, the buyer and seller, supported by their respective advisors, negotiate an agreed-upon working capital target, which is formally documented in the Share Purchase Agreement (“SPA”). At closing, the actual NWC is compared to this agreed target. If the actual NWC exceeds the target, the excess is added to the purchase price; if it falls short, the shortfall is deducted. This mechanism ensures that the purchase price accurately reflects the company’s true economic position at closing.

According to market practice, it is expected that the target will be acquired including a “normal” level of NWC which is assumed to be included in the enterprise value (“EV”). This ensures that e.g., sufficient receivables and inventory exist relative to payables and other current liabilities, allowing the buyer to continue operations without the immediate need for additional capital injections. Conversely, should the NWC exceed the normalized level at closing, the surplus is typically for the seller’s benefit, as it represents additional tied working capital beyond what is required for the ongoing operations of the business. This situation might arise, for example, if the company makes a large sale of e.g. a product shortly before closing, resulting in a significant increase in accounts receivables. While the cash has not yet been received and booked to the bank account, the associated value of the deal beyond normal working capital need does not fully belong to the buyer.

When correctly implemented, the NWC adjustment mechanism protects both sides: the buyer secures the necessary resources to ensure operational continuity without immediate recapitalization and is safeguarded from risks such as aggressive receivable collection practices by the seller (aim to increase the cash in bank account, as it is added to EV, NWC adj. corrects this to buyers benefit), while the seller is protected against e.g., unfair buyer gains from unusually high levels of receivables outstanding at closing as described above.

A useful analogy is the purchasing of a car: If no other arrangement has been made, the buyer expects not only the price to include the vehicle but additionally the gas tank to be half full to drive away safely.

Practical Challenges in NWC Determination

While the principle of NWC appears straightforward, practical application often presents multiple challenges:

- Which balance sheet items should be included in the calculation of NWC?

- How to ensure that the calculation (inc. selected time period) reflects the most accurate level of the company’s true operational requirements (“Normalized NWC”)?

- Have the monthly balance sheet items been properly accrued and fairly represent the business’s economic reality?

- Have seasonal fluctuations or one-off anomalies been appropriately considered?

Although certain market practices exist, there is no universally applicable model for all NWC calculations. Typically, historical monthly average NWC levels are used as a benchmark, but other factors must also be considered:

- Business Seasonality: For example, retail businesses experience significant working capital swings between seasons.

- Exceptional Situations: Unusual payment terms, delivery delays, or inventory clearances may temporarily distort working capital levels.

- Group Structures and Intra-Group Items: Intercompany receivables and liabilities must be separately analyzed and, where appropriate, eliminated from the calculation.

Experience shows that the best way to avoid post-closing disputes is to establish a clear, mutually understood calculation methodology early in the process, ideally documented already in the Letter of Intent (“LOI”). Doing so lays a strong foundation for smooth negotiations and minimizes the risk of late-stage transactional conflicts.

Conclusion

Although NWC represents just one component of an M&A transaction, its impact on the transaction’s outcome can be considerable. When properly structured, an NWC adjustment serves as an effective protection mechanism for both buyer and seller—but only if its details are carefully and expertly negotiated.

Therefore, we strongly advise all transaction parties to treat this topic with the seriousness it deserves and to engage experienced professionals early in the negotiation process.

Do you have questions about NWC in your upcoming transaction? Leave your contact details below and we’ll get in touch.